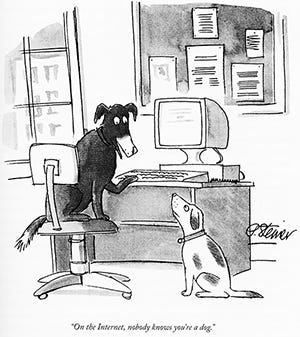

On the Internet, no one knows you're a human

The trajectory of AI spells the end of the social web

The next step in the AI arms race was recently taken by OpenAI’s Sora project, a major advancement in the company’s ability to produce realistic videos. Like many unfortunate browsers of the web, I watched a few of them. On the merits, they were only okay. Everything was slightly unreal, uncanny, hallucinatory, only physics-adjacent, with only a partial grasp of space and time, too saturated, too slavishly filmic, too much a self-conscious production of content and not enough a recording of reality. But separately from its technical qualities, and in a way I couldn't articulate at the time, it was more deeply troubling than any AI-produced media I had ever experienced.

This troubled feeling had a galvanic effect on me. I couldn’t sit at my computer anymore. I went outside with my daughters. We tinkered with their bikes, removing training wheels, pumping tires, bumbling around the driveway. I cleaned and organized my workshop. Later, I went back inside and rested at the kitchen table, watching a hand-painted birdhouse swing slowly in the breeze and the gathering dark, trying to make peace with what had troubled me so much. I had bounced, with some force, off of something in those videos. What was it?

Never critique the production of AI agents on the merits. We can all have a good laugh at ChatGPT missing obvious questions, or Midjourney giving its figures’ hands seven fingers, or at the hallucinatory physics of these new Sora videos. But using these shortfalls as critiques miss the point, because what do you say when the technical problems are resolved? The problem with AI is not that it is imperfect. The problem with AI is something else and something much more fundamental entirely than its technical accuracy. We risk accepting the basic premise of artificial intelligence by laughing at its mistakes.

For years, the ingress of filters and AI-enhanced modifications to online pictures and videos have severed valuable cords between the digital and physical social worlds. But AI video is soon going to get technically "good enough" to out-compete videos of reality. It is only a matter of time and effort. Don’t believe me? Consider the trajectory: look at AI images produced one, two, three, four, five years ago. Plot the line and observe the exponential. Any semblance the digital world has to the real world, any semblance digital people have to real people, is going to disappear.

Video killed the Internet star

This is much worse for us because the dominating medium of social media is video. More so than any other medium, video is what sells, hooks, sticks, and goes viral. Consider how Instagram, YouTube, Facebook, and TikTok, are now all, in whole or in part, infinite video feeds. They have all been brought, in some kind of attention-getting convergent evolution, to the conclusion that the infinite video feed is the way for them to maximize revenue. Even Twitter, a.k.a. X, feels the pull, and just a couple of weeks ago declared “X is becoming a video first platform.” Video has therefore eaten the digital world, leaving the dominating substrate of our social and civic lives utterly vulnerable to a silent takeover by unreality.

Communication technology has always done at least one thing: extension. We could reasonably extend ourselves into the world with the technologies of writing and printing, and then later speaking and recording, photographing or filming. We have built entire worlds on the technological, and now digital, social model: modes of government, of learning, of discourse, of business, of amusement. But in the age of Sora, this technology is no longer useful to us as an amplification of our ability to record, communicate, or seek the truth.

Why? First, it is impossible to compete for attention on a global digital platform against agents who are so much better at the mechanical aspects of ‘attention-getting’ — polish, dazzle, sex appeal, and an ability to understand and manipulate the black-box algorithm that decides what to show to whom. That we feel the need to compete on such terms, even with each other, is itself a social defeat of a profound nature. But to compete with impossibly complex and powerful models trained incessantly and at great cost to defeat us at that game is a losing proposition at the outset.

And if we want the attention of our fellow humans, the Internet is rapidly becoming the last place to seek it. Profile pictures can be generated ex nihilo. Backstories can be written for every conceivable permutation of online personality. Audio with a recognizable voice can be readily created out of just a few samples. And with Sora’s videos, the final desperate ways we have to find and verify truth online are dissolving. What are you going to do when you receive a video sent to you by someone you know, containing their voice and likeness? How certain will you be that it is them? If you see a video of a chaotic and rapidly-unfolding public event, how are you going to verify that what you see is actually happening? Watch more videos online?

Act III, Scene 1: Touch Grass

I might say that we are in the third act of a three-act play, a grand narrative that wheels around modernity. The first act was pre-modern. We were creatures, caught in the wash of our gods and our families and our land. Modernity gave us an escape in the second act; we could arrest the titanic forces of time, space, matter, and energy, and bend them to our purposes, to turn them into instruments. We could extend ourselves and our minds and our influence great distances, understand and heal disease and injury, walk on the moon.

Now, why bother going to the moon? Far more transcendent, vibrant, otherworldly, dopamine-suffusing and dazzling experiences will be available without effort. Why communicate with people over a great distance? It might not even be them, or it might not even be a 'them'. So perhaps, at the cusp of the third act, we will stumble outside, looking again for a way to get caught in the wash of something transcendent: our gods and our families and our land. But the gods are dead. Our families are small, insular, atomic, and distant. And the land is tamed, desertified, denuded both of its promise and its peril. This is why Ross Douthat, in his lament over Western decadence in The Decadent Society, pointed beyond the moon and to the stars for a potential source of inspiration in these latter days:

"...I suspect that a truly globalized civilization cannot help tending toward decadence so long as it remains earthbound, so long as there is no hope of finding actual new worlds to leap toward, conquer, or explore. I suspect that what we see happening in our society today--the turn toward simulations and virtual realities; the declining birthrates; the sense of repetition, stagnation, and futility--is connected on a deep level to the post-Apollo mission sense that such a hope does not exist, that there is quite literally nowhere else for mankind to go, that we are stuck here waiting to either destroy ourselves accidentally or to have nature hit reboot, via comet or a plague, on our entire up-from-hunter-gathering, east-of-Eden project."

There is the overwhelming sense that the world of technology, the medium through which we transacted everything in the second, modern era, has slipped its moorings and is drifting at sea under its own momentum, or that it is a rogue satellite, escaping the bonds of gravity and plotting its own trajectory into the stars. What drives it on? The new world it is building is not for us. We have the vague and uneasy sense that the use we get out of some app, service, or device is only its secondary purpose.

Technology companies talk about the possession of AI training data (the thoughts and feelings you convey via private message; the images you post, share, and like; the videos you record or watch) like nation-states talk about natural resources or weapons stockpiles. In the on-rushing wave of artificial intelligence, the winners will win because of the quality of the content they re-constitute from what you have given them.

But as time goes on, the models themselves will begin to be trained on previous versions of their own output. This regurgitating cycle can cause reality itself to drift bit by bit into something unhuman and unreal. What it is trained on resembles real life less and less with each passing generation. There are no reliable estimates for what percentage of text and image "content" churning through social media is the product of human hands and minds. But it is certainly dropping dramatically.

Rediscovering embodied life

What remains, stubborn and waiting for us to return to it from the hallucinatory drift of the online life, is flesh and blood. It is almost a truism for us by now, but ‘unplugging’ is meaningful and satisfying to us on the deepest level. Reality is tactile, solid, suffused with the fierce warmth of the sun and the sublime cool of the night. It encloses, deep within itself, a wholeness and oneness that we crave, even if we will only ever taste hints of it on this mortal plane. And it pricks us, too: that reality is tactile implies also the sharp edges of grief, the mordant slouch of disappointment, the tang of fear, the keening cry of want.

By contrast, the AI-powered digital world is a gauzy, numbing kaleidscope of fleeting impressions. It promises sensation without the sensuous, exhiliration without exaltation, promises kept without promises made. Like a siren song, the entanglements of digital content can entrap us and make us lost, render us inert, anesthetize us against pain but inoculate us against pleasure.

I felt something like a deep, pre-cognitive horror when watching the Sora videos, a survivalist jolt warning me away from danger, from a foe camouflaged but not yet perfectly hidden. We know what it means see or hear the unreal and call it real. We call it schizophrenia. What AI video may do for us is heighten the contradictions of digitally-mediated reality to the breaking point. It may expel us, blinking and flabby, into the light of day. I mean this completely seriously: it might make us touch grass. The very inhumanity and alienation of the Internet may turn us back to reality, and back to each other.

But consider what humans have done when asked to accommodate themselves to other machinery not conveniently designed for human bodies or human psychology. Our forebears broke their bodies on the machines of early industry. Our broad accession to the white collar world had us attending self-help seminars, reading pop psychology, or chemically altering ourselves to form us into sufficiently productive cogs in the professional-managerial machine. We fashion one-size-fits-all schooling systems for our children, and medicate away the protestations of those who do not fit. We go along to get along. We are social creatures. If history has any lesson for us, it is that there will be plenty of willing playmates for the automatons of the digital future, in part because of the shape of the Internet, and therefore the style of AI content, is social.

I fear that the social Internet will begin to resemble a digital Truman Show, the bots forming the bucolic backdrop to so many essentially staged interactions. Truman eventually found the door on the horizon, against the painted sky. Some are searching for it by escaping through the sky too, following Douthat’s prescription against anomie. Others are turning back time to the halcyon days of the second era, when the discovery of the laws of nature gave man great power over its forces, and discovering for us even weirder and wilder ways to exert control over nature. And there may be a gap, after AI gets good enough to enter the uncanny valley but not yet good enough to leave it and cast its spells, where more will see that the digital commons is no home for humans.

For my part, I found the door outside, in a world by turns too grimy, drab, disappointing, weird, tactile, surprising, and beautiful to be the work of anything but the hands of nature and nature's God. I pray that you, too, find the door at the back of the sky. Let’s make it a good third act.