Last month, I wrote about the ‘material’ reasons — political, industrial, and economic — that so many buildings are ugly. In case you missed it, you can read it here:

Why are buildings so ugly? Blame the process.

I feel a natural defensiveness when I hear contemporary buildings criticized for their beauty. I am not an architect, but I received a professional degree in architecture. Some of the buildings that draw public ire were designed by friends, contemporaries, or former employers. I can look at almost any building so criticized and still see the evidence of…

But we miss a lot of the story by focusing only on the blind processes and systems that produce ugly buildings. Some of it arises intentionally. Why?

A nation of sheds

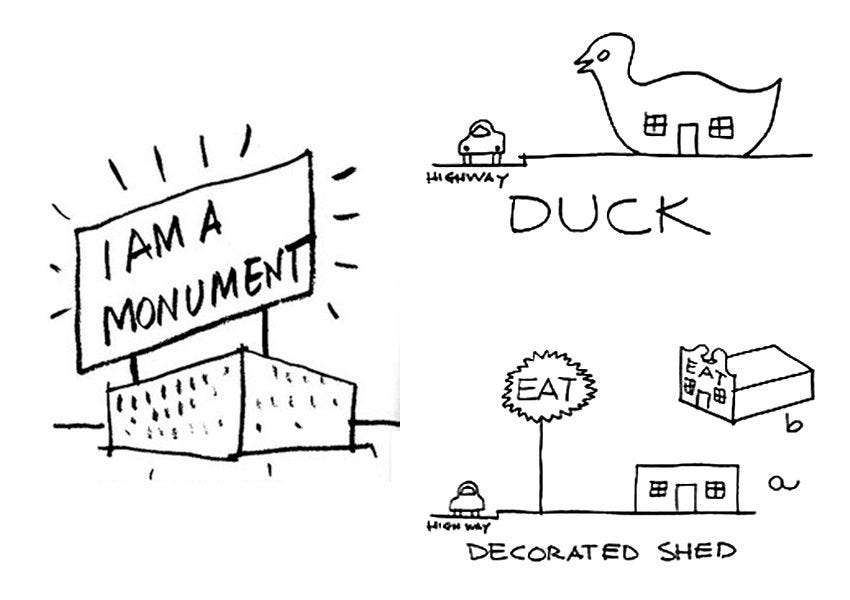

Robert Venturi and Denise Scott-Brown, in their essential study of American contemporary architecture, Learning From Las Vegas, coined the term 'decorated shed' for a building type they saw in their survey of the building stock of the United States.

Consider a typical American strip mall. If you walked around the large, long building, you would find that its side and back facades are completely different from its front. The front has large, imposing, decorative signs and ornaments. But on the sides and back, the boxy shape of the building is revealed in all its technical directness. This is the shed Venturi and Scott-Brown spoke of. The clean simplicity of the box is disguised by the appealing and immediately recognizable storefront. With the advantages of relatively cheap non-structural secondary framing, stucco, foam, paint, glass, steel, and aluminum, a designer can create nearly any mask for what is a coldly logical building lurking behind.

It is clearly not just technical possibility which makes this style of building so common. The very size and gaucherie of the typical decorated shed facade serves a purpose as a literal sign, because it can be spotted from a fast-moving car on a highway. The faster you go, the bigger, more direct, and more in-your-face the symbolism must get. In the car era, buildings have to up the ante to get the same amount of attention, even if the Best Buy storefront blares at you when you are on your feet in front of it.

In the same way, modern residential buildings put up signs of wealth, sophistication, and culture: fake shutters, balconies, dormers over garages, grand columns of foam and plastic, roof profiles not seen since pre-Revolutionary France, grand central gateways that can just be walked around. These houses are often not unique; they are built from a template used over and over again, thousands of times, across the vast new suburbs built since the advent of modern building materials and the car. Venturi and Scott-Brown do not defend the beauty of these buildings, but ask that we take them seriously as aesthetic works. The impulses which drive designers to design these buildings, and buyers to buy them, are real enough. And the choice to design in these conventional and ordinary ways, using symbols that are straightforward and easy to read, is an intelligible one. We want to project wealth, sophistication, culture, and also conventionality. And so we live in places that do so.

What does this have to do with beauty? Very little, directly. We have a mania for ‘authentic’ vernacular architecture, for forms and symbols that clearly spring from deep within the well of a rich culture. We travel great distances to see them. All that these two architectural theorists are trying to point out is that cheap, ugly, ordinary architecture is our modern vernacular. Its symbols and forms likewise hide deep meaning about our culture, way of life, and values. Venturi and Scott-Brown are at pains not to pass judgment on the architecture of the Las Vegas Strip or of the vast anonymous suburbs of Levittown.

“This viewpoint [criticism of ugly and ordinary architecture] throws out the variety with the vulgarity. In dismissing the architectural value of the Strip, it discounts also its simple and commonsense functional organization, which meets the needs of our sensibilities in an automobile environment of big spaces and fast movement, including the need for explicit and heightened symbolism. Similarly, in suburbia, the eclectic ornament on and around each of the relatively small houses reaches out to you visually across the relatively big lawns and makes an impact that pure architectural articulation could never make, at least in time, before you have passed on to the next house.”

[…]

“The critics of suburban iconography attribute its infinite combinations of standard ornamental elements to clutter rather than variety. This can be dismissed by suburbia’s connoisseurs as the insensitivity of the uninitiate. To call these artifacts of our culture crude is to be mistaken concerning scale. It is like condemning theater sets for being crude at five feet or condemning plaster putti, made to be seen high above a Baroque cornice, for lacking the refinements of a Mino da Fiesole bas-relief on a Renaissance tomb. Also, the boldness of the suburban doodads distracts the eye from the telephone poles that even the silent majority does not like.”

They may not pass judgment, but may we? We could reasonably expect the vernacular of a sick culture to be ugly, itself. Venturi and Scott-Brown, in the above passage, do not quite get there, but they point their fingers right at a few obvious culprits. We often resort to communicating with hilariously out-of-scale gestures glued to our houses. We derive meaning by decorating and differentiating ourselves, but we must do so overtly and dramatically to be noticed even at a fleeting glance. We are humans; we will always need to communicate to each other through the things we design and build. If that communication looks garish, tacky, and ugly, we ought to attend more to the culture which makes that form necessary.

So, what do architects do?

These big box stores and mass-produced tract homes are often not designed with all of the advantages of actual wealth, sophistication, and culture. The ‘low’ culture of tract housing and big box stores bespeaks cheapness and ugliness, buildings designed for the landfill. What does ‘high’ culture produce in response?

The earliest giants of modern architecture came up in the early machine age. It is hard to capture just how tumultuous and displacing this period of history was to every norm. Technological and cultural changes during this time completely upended the ways people lived, the activities they took part in, the work they did. So too did it change the dominant architectural references and milieu of the early modernists. Early modern artists and designers, like the Italian futurists, were obsessed with machine aesthetics, with speed and dynamism, and with building the new cities of the industrial future.

Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, and Walter Gropius had new references to draw on: the factory, the grain elevator, and the warehouse. What fascinated them about these buildings was how their deadpan functionalism laid bare to the eye the new industrial processes that went on inside. These buildings were icons of work, of production, of muscular and dynamic motion, of sublime and terrifying scale. They were evocative of the spirit of the age; an unbounded spirit. For all of human history to this point, the human was more or less on the brink of starvation, forced to scrabble for survival, with only marginal gains in security and stability. But in the heady early years of the industrial revolution and modernism, the Haber-Bosch process, the assembly line, and new forms of management had released entire cohorts of the human race to other activities. Humans, having looked down into the dirt for their sustenance for time immemorial, looked up and saw towering silos and belching smokestacks.

Studying processes and functions was intoxicating—and liberating—for these designers. They saw the power of mechanisms set loose to transform matter and exert energy. And this sublime and terrifying power inspired them to build buildings which themselves were the unavoidable outcomes of ruthless design processes. Again, Venturi and Scott-Brown:

Vitruvius wrote, via Sir Henry Wootton, that architecture was Firmness and Commodity and Delight. Gropius (or perhaps only his followers) implied, via the bio-technical determinism just described, that Firmness and Commodity equal Delight; that structure plus program rather simply result in form; that beauty is a by-product; and that—to tamper with the equation in another way—the process of making architecture becomes the image of architecture. Louis Kahn in the 1950s said that the architect should be surprised by the appearance of his design (Fig 118).

Presumed in these equations is that process and image are never contradictory and that Delight is a result of the clarity and harmony of these simple relationships, untinged, of course, by the beauty of symbolism and ornament or by the associations of preconceived form: Architecture is frozen process.

This is why critics call modern architecture navel-gazing and self-referential: because it literally is. The modernists created many compelling, sublime, and sometimes beautiful works of art, design, and architecture. But the beauty is a cold one, like the mathematical beauty of a geometric proof; an attentive viewer can see why the building arose the way it did, if they study it carefully and can have the secrets of its hidden process revealed. But it makes buildings, ostensibly places for people to live and work and play, into nothing more than a puzzle about the architect’s own motivations.

Early modernism was enthusiastic about the dynamism and activity of these new references. But the industrial might of growing nations could produce bullets as well as bread. Dada, a ridiculous and surreal form of art catalyzed by bohemian artists recoiling against the mechanical horrors and reactionary nationalism exemplified by World War One, poured their despair, dislocation, and trauma into absurd and irreverent works of art. Struggling with the contradiction, absurdity, technological forms of extermination and production, and parochialism of modern life, these artists responded with art that was extraordinary, brutal, profane, absurd, weird, and intentionally meaningless. This shockwave created ripples in art and design even into the postwar period. On this foundation was built mash-up and collage culture, pop art, punk, Postmodernism, and other essential building blocks of contemporary art history.

This history can only be poorly summarized here. But one descendant of Dada, Postmodernism, bears mentioning in more detail. Postmodernism in the United States built upon the trends in American design Venturi and Scott-Brown had identified, and took them seriously as precedents, as they had. By aping the ugliness and ordinariness endemic to the American suburban landscape, Postmodernism cast itself as the only sophisticated interpreter of contemporary culture. But it was in the end a fundamentally unserious style, playing with past forms and modern materials to create an ironic, grotesque, and gigantic mockery both of industrialism and of American kitsch. It galvanized a weird kind of zombie historicism spiritually similar to the saccharine nostalgia of Disney real estate. If the technical and cultural upheavals of the 20th century created of architecture both literal and conceptual rubble, Postmodernism made castles in the turned-up dirt.

The Metabolists and high-tech parametricists, almost the Oppenheimer to postmodernism's Barbie, took the technical and cultural environment of the 20th century much more seriously. Like their early modern counterparts, they were obsessed with process. But by the time of the Cold War, the nature of processes had changed. The paranoid, apocalyptic, high-tech style of the Cold War was their milieu. The ubiquity of early computational command and control interfaces, faceless bureaucratic monuments, and the growing international corporate style provided ample references for the designers of cities and buildings. The metabolists and high-tech parametricists devoted themselves to all the intellectual and technical possibilities that computer analysis, high industrialism, and mass customization could avail. These disparate approaches had formal references, but they were references alien to human and architectural history up to that point: the circuit board; the rhizome; the actual workings of computational machines; and generative, evolutionary, and biological processes.

Material culture is not morally neutral

It seems that each time I make reference to some reason for why so many buildings are ugly, I have to reach back to some cause that is not aesthetic itself: the vagaries of speculative real estate capital investment; the mass industrialization galvanized by scientific discovery; the psychological fallout of war and misery; Fordism; the advent of the car. This has been intentional. It would be a mistake to say that aesthetics were a second-order, unintended outcome of these movements.

Each of these political, economic, cultural, and technical phenomena was bundled up with a look and feel, with new styles of art and music and buildings and philosophy. It is not as if the aesthetic outcomes of these movements were incidental. The raw and commanding power of mechanical military might has inspired art, poetry, film, song, prose, and propaganda for all of human history. The masculine vitalism of the clanging machine has been rich fodder for industrialists and propagandists practically since they were invented. Car culture carries with it an entire pantheon of uniquely American visual references, styles, and aesthetics that bear not only upon the design of the car, but of roads, cities, buildings, and homes. Aesthetics were never the point of these cultural movements, but their look, feel, and sound were never accidental.

If the output of these titanic cultural and technical forces is ugly, even in an era of such material abundance, does it follow that this ugliness arises from something rotten at the very heart of technical and cultural modernity? The despots, warmongers, and slavers who underwrote, built, lived in, and worshiped in the great buildings of the past do provide a counterfactual.

But while I took pains at the beginning to point out that there may be nothing new under the sun, the legal, logistical, and economic forces that allow buildings of certain types to flourish have changed dramatically in the last two centuries. The Enlightenment, the advent of steel, the forces of industrialization, analytical methods of structural analysis, and a host of other changes that only took place in the last two hundred years have made the rate of aesthetic change so fast that maybe it only seems like things are fundamentally different now than they were.

Is there something new under the sun?

The burning question, for me, is whether this vast difference is an organic or an inorganic evolution; whether the buildings of the past and of the future rest on truly different foundations, or whether it is merely an evolution in style that, while that evolution is proceeding dizzyingly fast, is still just another predictable step.

Whether the rapid change we experience now is just a natural, eons-old process sped up, or the appearance of some new and malign force, appears also in my writing about food, war, and technology. But as it relates buildings, I have two concerns. First, exponential advances in technology have liberated design from constraint. The Bessemer process for the refinement of steel liberated the builder from the petty limitations of height and width, allowing them to build beyond the ordinary and into the extraordinary scale.

There was a time when material constraints meant that virtually every building could be taken in at a glance from a reasonable distance, and every building could be traversed vertically with nothing but legs and stairs. The net result of this material constraint was that buildings, and therefore cities, were ordered around the capacity of the human body to live and move within it.

The towering caverns of steel, glass, and concrete we can now erect are largely built from two impulses at best orthogonal to human life. First, we build just because we can, and second, because we judge buildings like optimization problems: how many offices, or apartments, can we pack together onto a single square of land? The seemingly arbitrary constraints of wood, stone, and clay, their tendency to be crushed under their own weight, given enough height, may have had the unintended effect of giving builders a natural constraint which roughly comported with what scale of building humans are psychologically comfortable with. Our new building materials have taken the lid off of the scope of our ambitions, but not off of our psychology. We are old bodies in new buildings, old wine in new wineskins.

Second, I am concerned that the conscious and unconscious aesthetic decisions we make truly have had their foundations switched out. That we have materialist explanations for bad aesthetic outcomes — ceiling tiles and flourescent lighting is cheap, concrete is so malleable, steel lets us span so much further and build so much higher — is itself not only a materialistic explanation. Maybe the point is that our new god is money, acquisitiveness, ‘the process,’ efficiency, modular reconfigurability, and that the aesthetic outcomes of our worship are obvious all around us. It is no surprise that a survey of the world history of architecture begins with sacred architecture — the Parthenon, Egyptian temples and pyramids, ziggurats, Shinto shrines, imperial palaces (themselves seats of god-emperors), the Florence Cathedral, St. Peter's, Notre Dame, the Norwegian stave churches.

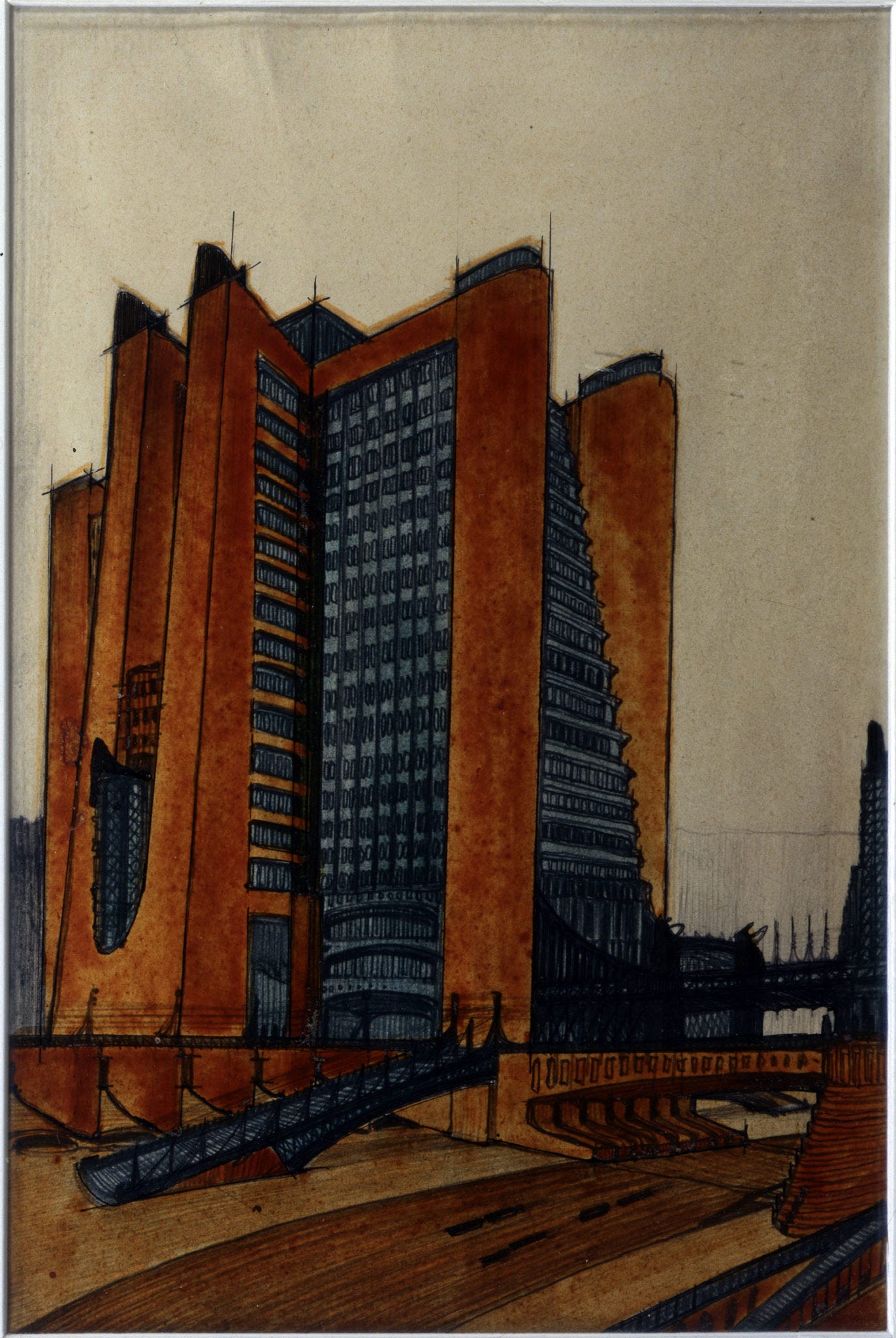

It is likewise no surprise where architectural history finds the starting point of modern architecture: the construction of the AEG turbine factory in Berlin, designed by Peter Behrens .With cathedral-like proportions and gigantic windows, it was no less monumental than its Catholic neighbors. But the choruses sung within its walls were the songs of clanging machinery. Its devotees did not bless themselves when they entered, but punched a time card. The icons in its shrines were forged steel. The factory was described variously by historians as a "temple of power" or as an "up-to-date edition of the Parthenon." Why describe it this way? A materialist explanation for the forces that gave rise to Behren's building is not incomplete, it is merely implying the new deity to whom the designers paid homage.

To answer the question, "is contemporary design different from the past by degree, or by kind?," these two points suggest that the work of the present is truly fundamentally different from the work of the past. Our new gods have, in their crystalline and mechanical wisdom, given us tools to build our own tower of Babel, and we have built them suitable temples. And many of them truly are beautiful. There will be works of architecture that have been built in the last one hundred years that will still be here in one hundred, five hundred, or one thousand years. But the worship of the new gods is not like the old. They demand monuments that occupy the heavens, not point to the heavens; the buzz of productive chatter, not the chant of hymns; an offering of all fruits, not just firstfruits. There is no lasting peace to be found in their halls.