A few months ago, I wrote this:

There is the overwhelming sense that the world of technology, the medium through which we transacted everything in the second, modern era, has slipped its moorings and is drifting at sea under its own momentum, or that it is a rogue satellite, escaping the bonds of gravity and plotting its own trajectory into the stars. What drives it on? The new world it is building is not for us. We have the vague and uneasy sense that the use we get out of some app, service, or device is only its secondary purpose.

Technology companies talk about the possession of AI training data (the thoughts and feelings you convey via private message; the images you post, share, and like; the videos you record or watch) like nation-states talk about natural resources or weapons stockpiles. In the on-rushing wave of artificial intelligence, the winners will win because of the quality of the content they re-constitute from what you have given them.

But as time goes on, the models themselves will begin to be trained on previous versions of their own output. This regurgitating cycle can cause reality itself to drift bit by bit into something unhuman and unreal. What it is trained on resembles real life less and less with each passing generation. There are no reliable estimates for what percentage of text and image "content" churning through social media is the product of human hands and minds. But it is certainly dropping dramatically. (On the Internet, no one knows you’re human)

This month, I am going to unpack something I only hinted at here: that our daily interactions are, very often, already part of the substrate of data on which artificial intelligence is built. We are producing the training data in every facet of our lives, and AI is reading, listening, and watching.

The most obvious examples, so far, have been in text, image, and video. We have all seen AI-generated text. In fact, we probably see it far more often than we think we do. Cheap copy is already the oxygen of the ad-driven web, and large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT or Claude have already made the production of such copy of trivial cost to the attention-seekers of the Internet.

But think more about what it took these companies to develop such technology. If you have ever written something and posted it publicly (or sometimes, even privately) online, the chances are quite good that your writing has been aggregated by one or more large language models. If you have written enough, or written publicly enough, it would also be fairly simple to ask a large language model to produce work on any topic in a plausible facsimile of your writing voice and style.

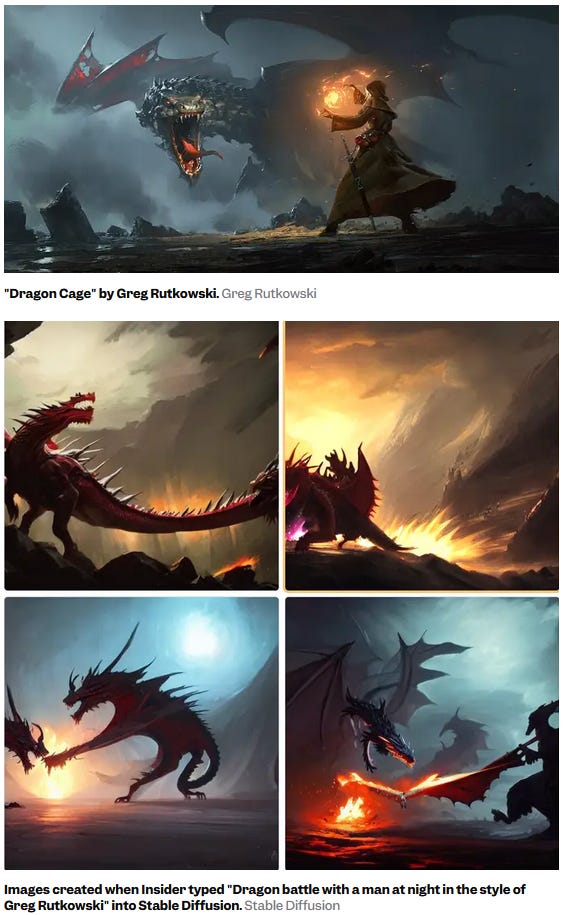

The same is true of images and videos. The thousands of pictures and videos the average Internet user uploads to social media site or photo sharing sites like Flickr likewise provide grist for the content mill, too. Artists and filmmakers eager for exposure have for years turned to the Internet to develop a following, only to find now that, without an agreement of any kind, thousands of cheap but believable copies of their artistic sensibility and style can be (and are regularly) produced by those who want their own version of the artist’s work, but do not want to have to pay the artist for it.

Here’s a related question: how many videos of you are taken every day as you go about your life? The miniaturization of camera lens technology and of storage has made it easier than ever to cover the world in array of sensors, capturing high-resolution video of your daily life and interactions wherever you go. Visit a friend? Wave to the Ring camera. Drive down the road? Dash cameras, LiDAR scanners, and stoplight cameras are all watching. Walk across the street? As cars watch you cross, modern cars use a huge array of visual and non-visual sensors to analyze your body and predict your behavior in order to avoid colliding with you. And for that, I suppose I am grateful.

Perhaps you believe in security through obscurity. Sure, you say, you are recorded on any number of convenience store CCTV systems, but if the cameras even work, who is going to dig through the old VCR tapes, play through them, and spot a grainy version of you in the corner as you buy a coffee? And unless you are being investigated for a crime, how likely is that scrutiny anyway?

Unfortunately, this picture of the world is hopelessly outdated, based on a generation-old view of technology you might have picked up from a cop show or period-appropriate movie. The surveillance technology of the present day looks far different. Not only are cameras much smaller, much more plentiful, and record at a far higher resolution, but forget the dusty box of tapes on the manager’s shelf. These videos are usually uploaded to massive and centralized datacenters, and usually not for the use of the owner of the camera. Here’s one way to think about it: if the manufacturer of a security system advertises that you can check their cameras from anywhere in realtime, it is almost always because those videos are streamed instantly to the security company’s own servers.

And many new cameras come with LiDAR, “light detection and ranging.” Think of it as a laser-based form of radar. It dramatically improves the quality and accuracy of surveillance cameras, working in the dark, sensing depth, and allowing AI-powered systems to detect, classify, and track objects.

Let’s return to the 90s-era cop show. A detective looking for a clue has to sit down at the tiny monitor and scrub through grainy video data for hours, probably chain-smoking or munching fast food, until seeing the tiny detail that eluded his first dozen viewings of the tape. Now? Simply query the vast dataset of video, and ask for clips of a middle-aged woman wearing a red sweater, or for any clip containing a black backpack, or search for a particular face or other identifying feature.

I cannot emphasize enough how much research and money is going into ‘computer vision,’ the technology helping algorithms look at a hopeless jumble of pixels (the videos) and discern from it shapes, objects, faces, movements, mood, emotion, intent. You are almost certainly part of the training data already.

Naturally, this realization can be uncomfortable. What if you want to opt out of being a human guinea pig for the rampant experimentation with AI invading every corner of our lives? Unfortunately, there is no “do not train on me” list akin to the do-not-call registry. But if you are worried, consider ‘living illegibly’ to opt out of training your replacement.

A field guide to living illegibly

Here is some grounded, practical, and actionable advice for avoiding the gaze of AI:

Put away the smartphone, or put it in a Faraday cage. Before approaching anyone else, ask them to do the same.

Never communicate with anyone through any medium other than analog methods. Meet up in person (away from cameras and microphones, of course) or send them a letter.

Don’t visit anyone with a Ring camera.

Don’t visit anyone with a smart home device. If you’re ever unsure, just say “Hey Alexa” or “Hey Google” and see what happens.

Don’t take pictures of yourself or your loved ones or of anything else, unless you’re using a film or old-school digital camera. Don’t visit Walgreens to print them out, either. See it on a screen? So does the AI.

If you are an artist, defeat AI by sticking to drawing, painting, or sculpting. Never use any Adobe product. Consider secret, no-cameras-allowed art shows and restrict your sales to utterly private collections. If you find that this puts a dent in your popularity, consider subtly poisoning the images you upload to confuse image models.

If you have to write or speak in a way that will be recorded and put online, be sure to utterly obscure your real meaning by speaking elliptically, using bizarre mixed metaphors, employing inexplicable irony, and changing your style of speaking and writing essentially at random.

And if you absolutely must go outside, do the following:

If you must speak in the presence of microphones, try to jam them using a highly-directed ultrasonic frequency. But be cautious: this might be illegal?

Cameras are difficult to avoid, but the good news is that you can upgrade your wardrobe and makeup. Choose some AI-defeating clothing like these rad sweaters, and some Juggalo face paint goes a long way. Caution: if you get run over by a Tesla, that one is on you.

Put a rock in your shoe, but always make to choose a different spot each time. Researchers have discovered how to recognize people just by their gait! A randomized limp should do the trick.

Taken together, these techniques will slightly confuse automated systems and perhaps real human engineers, and what’s more, you will look cool doing it.