In 1957, John D. MacDonald published his novel The Executioners, a shocking psychological thriller about a lawyer stalked and harassed by a a vicious rapist he had put in prison years before. Hollywood has taken two bites at this apple: once, in 1962, when Gregory Peck played Sam Bowden the lawyer and Robert Mitchum played Max Cady the psychopath; and again in 1991, when Martin Scorsese cast Nick Nolte in the role of Bowden and Robert De Niro as the violent Cady.

Mitchum and De Niro could not have been more different in their characterization of Cady. Mitchum famously made no special attempt to embody any part he played. Richard Brody wrote in 2014 that "Mitchum was, in effect, wilder than his characters; he endowed them with his own fury for life."1 He disdained so-called method acting, saying "They've been nowhere and seen nobody... these Method guys, they've done nothing."2 De Niro, on the other hand, let his roles swallow him whole. He was a Method man par excellence: for Cape Fear, he even paid $5,000 to have his teeth ground down (and another $20,000 to have them corrected), to better portray the obsessive menace on screen.3

In a nod to the silver screen superstars who had acted the pair in 1962, Scorsese gave Peck and Mitchum cameos in the 1991 remake. The elder Mitchum, playing a bit part as a detective observing Cady during a strip search, looks over De Niro's muscular, tattooed body, and mutters "Sheesh. I don't know whether to look at him or read him."4 Was Mitchum expressing disdain for the way De Niro aggressively animated his character, or was the detective commenting on Cady? Remember, Mitchum always played himself.

The art critic Dave Hickey, in his obituary of Robert Mitchum, made the same comparison between the late great actor and the new Cady, Robert De Niro. Writing for Perspecta, Robert Somol and Sarah Whiting have this to say in summary:

There are two kinds of actors, Hickey argues. First are some who construct a character out of details and make you believe their character by constructing a narrative for them. One could say that this is the school of the "Method", where the actor provides gesture and motivation, and supplies a sub-text for the text of the script. The second group of actors create plausibility by their bodies; Hickey says they are not really acting, but rather "performing with a vengeance."5

Somol and Whiting call these approaches "hot" and "cool," respectively. They were not the first; they borrow from the media theorist Marshall McLuhan's description of hot and cool media, itself a distinction lifted from the mid-century ethnologist Claude Lévi-Strauss's description of cold and hot societies. But do not get lost in the game of intellectual telephone. "Hot" means anything preoccupied with its own legibility. It is high-fidelity, intense, obsessed with form and technique, and intent on being perceived as different, against the grain, and in the foreground. "Cool" is anything relaxed, content with being background and anonymous. It allows and even invites speculation, participation, and re-interpretation.

In summary: "Cool is relaxed, easy." Doesn't that sound nice? Ah, but if only easy was actually easy.

We’re making a lot of hot buildings

Let's take a simple example: personal style. It is natural to want to be stylish, but it is gauche to obviously try to be stylish. We want our style to be understated, unbothered, effortless, smooth, natural, and above all to not be seen as trying too hard. Style can't be manufactured, it can't be obsessed and fussed over; it has to ooze. And so, of course, we get "hot." We obsess about not looking obsessive. We put in a great deal of effort to appear effortlessly put-together. We go to unnatural lengths to be natural. Our apparent understatement states quite a lot about us.

Somol and Whiting identified traces of this "hotness" in 20th-century architecture. It was obsessed with making what they called ‘critical’ architecture: a kind that revealed the process of its conception, that afforded and invited translation and analysis and a critical eye. It was architecture to be talked about, with the looming presence and intention of the architect always hovering in the background. It was incredibly self-conscious architecture: aware of its surroundings, aware of its critics, aware of its intent and of the various possibilities of its interpretation.

Naturally, the largely 20th-century built work of the critical architects reveals much about the stereotypical auteur. They are (and their buildings are) neurotic, hyper-aware, intensely diagrammatic, process-obsessed, seeking a defensible position in the swirling battlefield of critical theory.

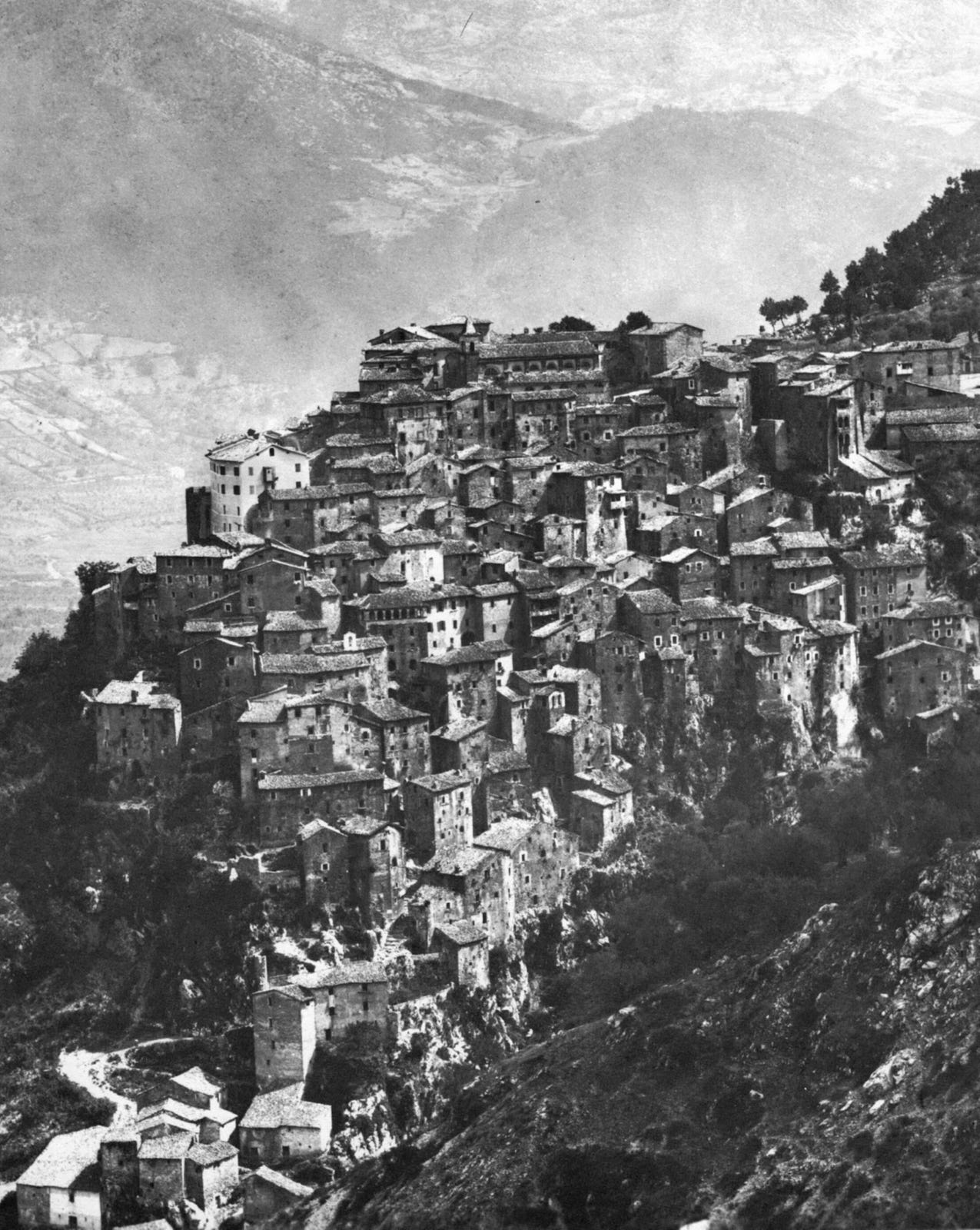

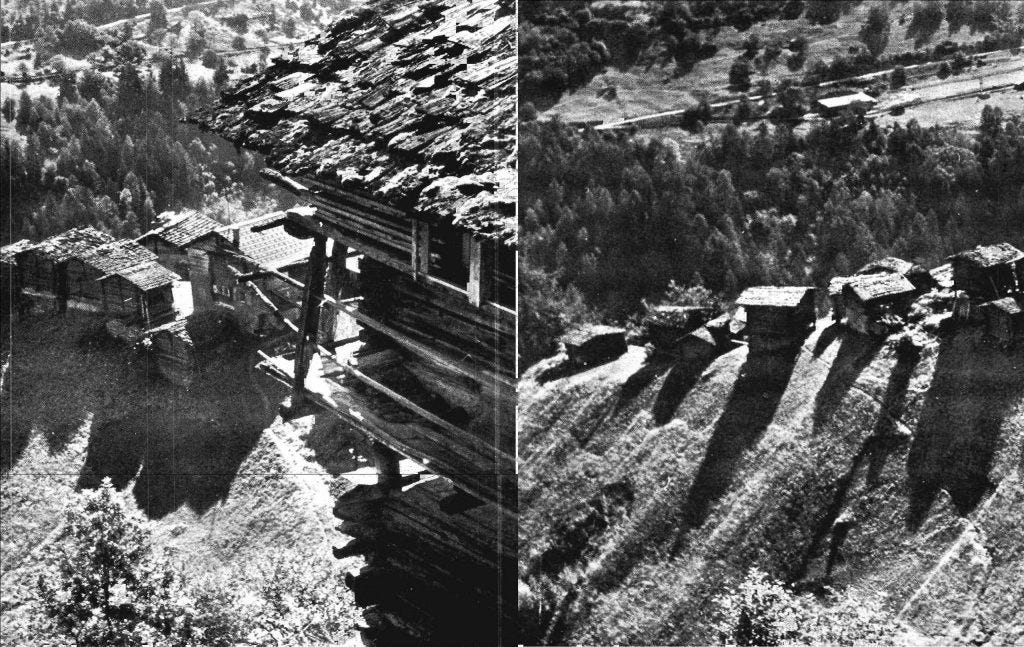

Isn't there a better way? Haven't humans built suitable and beautiful dwellings for themselves for thousands of years? We know what these places look and feel like: they seem appropriate, in keeping with their surroundings, suited well to their uses, arising authentically and almost spontaneously from local materials, culture, and vernacular. We love and revere them because they are whole. In other words, these places are...cool.

They are relaxed, content, unhurried and unbothered. They open up more possibilities than they preclude. They are not un-opinionated; like any built work, they enclose space and foreclose anything too far out of line. But their constraints seem to arise naturally from the needs and wishes of their makers and users, not from the obsessive mind of a process-obsessed designer with a critical-theoretic bone to pick.

Bernard Rudofsky summed up this attitude well:

Hence, a town that aspires to being a work of art must be as finite as a painting, a book, or a piece of music. Innocent as we are of this sort of planned parenthood in the field of urbanistics, we exhaust ourselves in architectural proliferation. Our towns with their air of futility, grow unchecked—an architectural eczema that defies all treatment. Ignorant as we are of the duties and privileges of people who live in older civilizations, acquiesce as we do in accepting chaos and ugliness as our fore-ordained fate, we neutralize any and all misgivings about the inroads of architecture on our lives with lame protests directed at nobody in particular.6

It is easy to come away from this topic with the overwhelming feeling that we have lost our innocence; that at some point we were unmoored from the culture of constraint and craft that informed our buildings. Now, when we put pen to paper, some vile instinct inveighs against our better instincts, intoxicating us with the strong drink of our latter-day power over matter and energy. In that spirit we create, but our creations reveals the tracings of our self-consciousness. In the words of the serpent in the Garden of Eden, we have eaten of the fruit of the tree in the midst of the garden, and now our eyes are opened, and we are as gods, knowing good and evil.

Like Adam and Eve sewing fig leaves together, we reveal just how hard we are trying, in our attempts to reclaim the easy and relaxed vernacular of our built past. Re-treads of traditional architecture tend, like Frankenstein's monster, to be not quite right: disproportionate, ungainly, revanchist, and kitschy; new wine in old wineskins.

Like I said, fatalism is an easy destination. But it is not quite the right response. If the story is to be believed, Adam and Eve ate of the fruit at the beginning of history, not in the twentieth century. It is better to say that the hyper-growth of everything (population, energy-producing technologies, information exchange) has both amplified our capacity to do things, and our capacity to learn about what others are doing. And those things aren’t always good.

How do we cool things down?

So how do we cool things down? You must forgive the irony of trying to cool down (or of writing about it). Remember our example about style. Suppose it could be done. How would we go about it? The architect and theorist Christopher Alexander, writing in The Timeless Way of Building, gave some cryptic advice. He recognized this same sickness of "hot" architecture:

In our time we have come to think of works of art as "creations," conceived in the minds of their creators. And we have come to think of buildings, even towns, also as "creations"— again thought out, conceived entire, designed. To give birth to such a whole seems like a monumental task: it requires that the creator think, from nothing, and give birth to something whole: it is a vast task, forbidding, huge; it commands respect; we understand how hard it is; we shrink from it, perhaps, unless we are very certain of our power; we are afraid of it. All this has defined the task of creation, or design, as a huge task, in which something gigantic is brought to birth, suddenly, in a single act, whose inner workings cannot be explained, whose substance relies ultimately on the ego of the creator.7

And despaired of every technology for conceiving of designs, even as primitive as pen and paper:

Only in the fluidity of your mind can you conceive a whole. [...] This can only happen if the design is represented in an utterly fluid medium; it cannot happen in any medium where there is the slightest resistance to change. A drawing, even a rough drawing, is very rigid—it embodies a commitment to details of arrangement far beyond what the design itself actually calls for while it is in an embryonic state. Indeed, all the external media I know—sand, claw, drawings, bits of paper lying on the floor—are all far too rigid in this same sense. The only medium which is truly fluid, which allows the design to grow and change as new patterns enter it, is the mind.8

But Alexander insists that this wholeness of design is achievable, and provides a few hesitant pieces of advice. For one, he advises us to trust our instincts, and the instincts of those who have gone before us. "...[H]uman beings are not so malleable...the fact that it comes into being is a fundamental fact about human nature in urban situations. There is little purpose in saying it would be better if this force did not exist. For it is does exist, designs based on such wishful thinking will fail."9 Buildings and cities can only achieve a pale half-life when they ignore the humans meant to live in them.

Nor could this wholeness and order emerge from top-down design. Alexander pointed to the emergence of complex forms in biology as an example of the higher and living order, and infinite complexity, that can only arise from many thousands of humans ordering their own lives. From the individual and anonymous actions of many can, over time, come forms and structures appropriate to their surroundings and their creators.

Naturally, this design methodology is allergic to ego. It is hard to try to be cool, and so Alexander helpfully recommended that we stop trying so hard. Of "hot" design, Alexander said: "These places are not innocent, and cannot reach the quality without a name, because they are made with an outward glance. The people who make them the way they do do because they are trying to convey something, some image, to the world outside. Even when they are made to seem natural, even their naturalness is calculated; it is in the end a pose."10 If only it were so easy! Haven’t we all already eaten the forbidden fruit and had our eyes opened?

Many others recognize this phenomenon of "hotness," whether they call it overthinking, getting stuck, or freezing up. And there are a variety of recommendations from pop psychology and self-help for dealing with it. You might call one kind of approach ‘jamming’: If you find yourself doing something you suspect is unnatural and contrived, don't try to relax or forget as a way of snapping out: just do the opposite, no matter how counter-intuitive. And, of course, you could micro-dose psychedelics as a way to jump-start your ego death and get un-stuck.

Mastery as antidote

But there are better ways. I urge you to watch the national sevens rugby team of Fiji at your earliest convenience. The game of sevens rugby is one of the most comprehensively demanding sports. Physically, it requires both raw power and incredible endurance. Mentally, it is a game of milliseconds; largely improvisational but highly technical. Different national teams play with different styles, and Fiji plays as “cool” as it gets. The Fijians are not using pop psychology to keep from locking up or playing tight. They play with a seeming effortlessness because they have utterly mastered their craft. As it is the de-facto national sport of Fiji, children grow up tossing around the ball almost before they can walk, developing a sense of the game that is mastered and perfected as the best players represent their country on the world stage.

Mastery makes effort invisible. It is why a Fijian rugby player looks like they are floating or dancing through defenses as they move across the pitch. Developing mastery is not a process of forgetting, or of losing touch with the basics of one's craft. It is practicing and practicing until that craft becomes a part of one's nature. This does not necessarily require hyper-specialization, but it does require focus, discipline, and time.

On the other hand, Sarah Whiting and Robert Somol suggest what they called "projective" architecture: design which states less and suggests more. This kind of architecture invites participation to complete it. It is atmospheric; it assumes that the building and its user will exchange content and context. In summary, cool buildings don't try to do too much. They are not as opinionated and do not try too hard to direct the activities of their occupants.

It is hard to describe these kinds of buildings in abstract terms. But we know it when we see it. We have been in buildings and places like this: places where we felt free and relaxed and felt the openness of the place to possibility. Many of the plazas of medieval cities have this effect. So, for that matter, do tailgates and blanket forts, or airline terminals during a long flight delay. These places don't try too hard. They are made alive by many small actions, and inflected by many small details.

Is there a through-line between mastery and deliberate open-endedness? I think Somol and Whiting would argue that there is. They were not so dour about the prospects for architecture as a discipline as Rudofsky was. On the contrary, they defended design as a discipline where mastery over difficult and open-ended qualities should be sought, and could be achieved:

So when architects engage topics that are seemingly outside of architecture’s historically-defined scope — questions of economics or civil politics, for example — they don’t engage those topics as experts on economics or civic politics, but, rather, as experts on design and how design may affect economics or politics. They engage these other fields as experts on design’s relationship to those other disciplines, rather than as critics. Design encompasses object qualities (form, proportion, materiality, composition, etc.) but it also includes qualities of sensibility, such as effect, ambiance, and atmosphere.11

What does it actually take to be cool?

This description of “coolness,” or what Alexander calls “the quality without a name,” is frustrating. It is described almost in dispositional terms: that one must have the perfect posture of the inner self if one is to be cool, to produce beautiful and effortless places for people to live, work, and play. Somol and Whiting do not suggest how to develop this posture. But we could summarize the Fijians, and Alexander and Rudofsky, and the pop psychologists, in just a few words.

To be cool is to focus on developing a mastery over craft, not obsessing with the outcome of that mastery. The cool practitioner does not begin with the end or intended effect in mind. Doing so in the public gaze makes it difficult to develop the disposition required to be cool, because one is inevitably drawn to see themselves in the third person. Social media is an absolute torment for those aspiring to coolness and wholeness, because it amplifies the innate tendency toward self-consciousness to a fever-pitch. Instead, sowing craft, focus, and time will reap coolness, in its own time.

The biography of the actor Robert Mitchum suggests that, when he acted, he drew on his colorful and varied life experience to bring himself to his characters. De Niro was quoted as saying that he immersed himself in his characters the way he did because it was a way to explore lives without having to live them. Mitchum would have scoffed. He lived those lives with gusto. To use a language of self-consciousness, we might say that Mitchum was exploring, in Cape Fear, what he would have been like as an aggrieved maniac. De Niro was exploring what the Platonic form of the aggrieved maniac might look like to a theater audience. But De Niro has aged, and lived, and now in his latter years seems to bring the gravitas of an experienced human, fluent in all of humanity's foibles, to The Irishman and Killers of the Flower Moon, his most recent collaborations with Scorsese. In his later days he has relaxed, letting the mastery he has achieved over the expression of the varied human condition to inflect his performances with the ease and effortlessness missing from his muscular, aggressive performance in Cape Fear. Being cool took time and practice for him, as it will for us.

Brody, Richard. “Is Method Acting Destroying Actors?” The New Yorker, February 21, 2014. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/is-method-acting-destroying-actors.

Johnston, Ian. “Robert Mitchum - Hollywood Outsider.” Louder Than War, June 17, 2011. https://louderthanwar.com/robert-mitchum-hollywood-outsider/.

d’Arcy, Susan. “De Niro’s New York Hotel.” The Sunday Times, March 16, 2010. https://www.thetimes.com/article/de-niros-new-york-hotel-ctmnz7sfvzr.

“Cape Fear Script - Dialogue Transcript.” Script-o-rama. Accessed September 9, 2024. http://www.script-o-rama.com/movie_scripts/c/cape-fear-script-transcript-scorsese.html.

Somol, Robert, and Sarah Whiting. “Notes around the Doppler Effect and Other Moods of Modernism.” Perspecta 33 (2002): 72–77. https://doi.org/10.2307/1567298.

Rudofsky, Bernard. Architecture without architects: An introduction to nonpedigreed architecture. London: Academy Editions, 1964.

Alexander, Christopher. The timeless way of building, 301. New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1979.

Alexander, Christopher. The timeless way of building, 510.

Alexander, 536.

Alexander, 536.

Somol and Whiting. “Notes around the Doppler Effect and Other Moods of Modernism.” 2002.

Interesting, John … thanks. My frame of reference on being “cool” vs. “hot” is the difference between what I call Inside-Out vs. Outside-In. Inside-Out means I’m “cool” on my identity (it’s known, comfortable and I’m not giving effort toward finding it), so I focus my energies living it effectively in my environment. Outside-In means I’m “hot” on my identity (it’s vague and conflicted), so I expect my environment to define who I am and I waste a lot of time and energy hoping to discover who I am—but I can’t ever find it because I don’t even know what I’m looking for. “Cool” identity is better! :)