Who's afraid of counting things?

As it turns out, witches are. Read on!

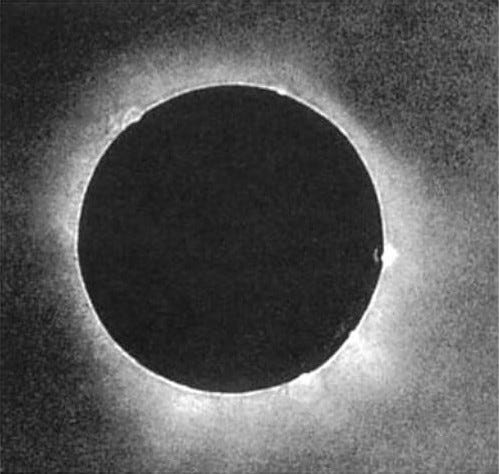

On July 28, 1851, at the Royal Prussian Observatory at Königsberg, Johann Julius Friedrich Berkowski aimed a retrofitted telescope at the sky and exposed a daguerreotype plate for eighty-four seconds. Above him, during those eighty-four seconds, the moon eclipsed the sun, allowing him to capture that rare astronomical phenomenon. The resulting image is spectacular: a circular black void, rimmed with the glowing corona of the sun's atmosphere, in stark black and white.

Total solar eclipses are epochal events in human history. Before astronomers could predict them, folklore readily supplied answers. The sun figures prominently in the mythology of basically every traditional culture, and who can blame them? It brings warmth and light and new life. Total eclipses were regarded as wars against the gods, as tricks of the evil one, as the reuniting of lost lovers. But Berkowski took every rambling meaning of that event, and indeed the gyres of the very god and goddess of the sky, and skewered them remorselessly on a sheet of silver-plated copper.

In The Rise and Fall of D.O.D.O., a work of speculative fiction by author Neal Stephenson, it was this fateful photograph that wrung out all of the magic in the world. His explanation riffs on quantum physics. Something that is in a quantum state has an air of mystery, or indeed of magic around it. Physicists call it 'superposition,' but think of it as uncertainty. We may know a particle is out there, but we don't know precisely where it is or where it's going. The tricky thing, however, is that whenever we catch a glimpse of it, the very act of observing it collapses all other possibilities about it. It suffers 'wave function collapse'—whenever it finally interacts with the outside world, all of the potential and probability and mystery about it ends.

At every total solar eclipse before modern astronomy, people along the path of totality had looked up surprised, caught in the awe and wonder of an inexplicable and terrible natural phenomenon. By 1851, however, sun and moon were firmly pinioned to a static, immutable record. This stole the magic from the world: the fact of the eclipse was no longer a superposition of fantastical possibilities in the minds of every observer, but a single and incontrovertible fact burned into a plate in Prussia. And for Stephenson's D.O.D.O., no witch's incantation could have any more effect after that moment.

The Magic Has Gone Out of the World

This narrative is compelling because it speaks to something real. There is something deeply amiss about the modern world, something sterile, prescribed, and controlling. I have sensed it, and I am sure you have as well. Dissatisfaction with modern life is a common enough trope that it appears with regularity in movies, TV shows, and books like D.O.D.O. Modern life feels fragmented and harried. Whether it ever existed or not, many people, myself included, are tempted to feel a powerful nostalgia for a past that was whole, integrated, authentic, and free.

In part it is because modern life is bewilderingly complex. We all specialize in our little niches. This lets us go much further and build up more detail in our own areas of expertise, but at the cost of not knowing what everyone else is up to. That can make other fields and forms of knowledge inscrutable to us, even as we outsource more and more of our lives to experts whose competency goes far beyond our own. Despite how specialized experts in their field become, we grow wary of them. They are gaining control over our lives, but we are not gaining a commensurate level of understanding about their work. We depend on them, even as we mistrust them—often for very good reasons.

This dependence is not because they retain any hard coercive power over us but because they have been so singularly effective. Under their management, nearly every conceivable measure of human well-being—health, longevity, wealth, leisure, educational attainment—has skyrocketed. Across the right timescale, the graphs resemble hockey sticks, with a rapid and asymptotic rise even as experts gained dominance.

There are many names and as many motivations for these archons of expertise. We call them empiricists, materialists, stats jockeys, technopolists, devotees of 'scientism,' the professional-managerial class, experts, elitists, geeks, nerds. These terms are overloaded, and none of them are useful for describing this phenomenon in general. I will therefore call them the numerate, or those who practice numeracy. They are adepts at capturing information, classifying it, analyzing it, and drawing conclusions from it. My use of the word numeracy is not to obscure the issue but to clarify it: we should treat numeracy like we do literacy. Literacy is more than being able to read; it is a way of thinking and processing information dominated by the written word. It transforms psyches and moves nations. So too is numeracy a way of thinking dominated by numerical methods. And like literacy, it changes us individually and collectively.

Our skepticism of numeracy has metastasized into actual distrust. Much of the political and cultural upheaval of the past sixty years (and indeed, the past five) can be seen as a tacit rebellion against experts and the very notion of expertise and disembedded knowledge. Public health, peer-reviewed scientific research, research-oriented government agencies and universities, and modern methods of chemistry, biology, and agriculture, are outré. The institutions, caught up in embarrassing missteps and conspiracies, are reeling. The state of scientific publishing is abysmal. The information ecosystem surrounding health, nutrition, psychology, and behavior is a disaster. And on the rise, correspondingly, is magic. The growth of the spiritual-but-not-religious, the rapid mainstreaming of astrology, the resurgence of woo in all its forms, are all testaments to the failures of the numerate and the re-assertion of folkways, folklore, and folk cures.

To be clear, this is a slow-motion disaster. Without care, we risk reeling from one error into yet another, like a child smashing his entire block tower in frustration when a few pieces fall. Europeans tired of the social upheaval galvanized by the printing press and the dawn of the literate age would have been forgiven for looking askance at the literate. But it would have been a mistake for them to shutter the schools and smash the printing presses.

We therefore undertake a dangerous task when we rebel against the depredations of the numerate, for our task is painstaking and surgical. First, we must understand the problem behind the problem: not just that numeracy has given us misguided public health advice or paternalistic algorithms, but something more fundamental has gone wrong. Second, we must stake out some natural limits for the practice of numeracy. Finally, we must articulate the positive good of numeracy and suggest an end toward which it should strive.

I. The Resentment of Control

I became a teenager in the early days of cell phones and text messages. It was during this time that some friends and I learned about an SMS-based service called ChaCha. If you texted 242-242 (CHA-CHA in the old T9 parlance) a question, you'd get a fairly accurate response within a minute or two, accompanied by a few text-based ads. By 2006, when it launched, we all knew what Google was and how easy it would be to find information, but you couldn't search Google unless you were sitting at your computer—something that (at that time) we were not doing. Instead, you could text this number, and it would connect you to someone across the world who could presumably Google the question on your behalf and text you back the answer. So when some disputed fact came up in conversation, we could just text ChaCha to resolve the dispute. We had our fun with this: asking nonsense questions, proposing marriage to the hapless Googler on the other end of the line, capriciously arguing with their answers. But gone were the days when we just…wouldn’t know.

If you live in the modern West, you have almost completely forgotten about the fundamental impenetrability of the stuff of the world. You do not remember the world as it was: draped in gauze, pregnant with suffocating mysteries, wholly out of your ken. Today we are delivered predictions, estimates, and forecasts with such regularity that we do not count the uncertainty inherent in the world as it is. But it is all provisional: an addition made to us after our creation.

In the time before mass information, it was supremely difficult to generalize about particulars. What conclusions could you draw from what you experience? Life was so bewildering and incomprehensible to begin with, so changeable and without any cause obvious to you, that it was no wonder that the nature of what knowledge developed during this time was provisional, applied, empirical, embedded, and frequently wrong—even if the consequences of its wrongness were limited.

Numeracy cracked open the world. If the heavenly bodies were mechanisms, if trees were great biological machines for the production of lumber, if the muscular neck of a river could, like a snake's, be grasped and pinned down for all time, then these forces were no longer actors in the grand drama of the living world but props and sets for we actors to compose and play around. This was the power of the new sciences, for in discovering the mechanisms of the world around us we could suddenly place things in their way or get out of it ourselves, and so wring the mystery and its attendant danger out of the world.

A. Subject to Object

It is no wonder that in the pre-numerate time, things of all kinds tended to be subjects, actors in the grand narrative of life, not objects to be exploited and manipulated. Chief among the subjects of the past were the heavenly bodies: sun and moon, stars and comets. The turning of seasons and changing of weather, the way the leaves of trees turned up as one to catch the rain or how the birds heralded a coming storm only confirmed that the whole world was one heaving mass of actors, advancing and retreating before forces arcane and ancient.

The wholesale conversion of the world from subject to object, from actor to set or prop, is not without consequence. In an essay on the work of German philosopher Martin Heidegger, Mark Blitz wrote:

Introducing the Bremen lectures, Heidegger observes that because of technology, “all distances in time and space are shrinking” and “yet the hasty setting aside of all distances brings no nearness; for nearness does not consist in a small amount of distance.” The lectures set out to examine what this nearness is that remains absent and is “even warded off by the restless removal of distances.” As we shall see, we have become almost incapable of experiencing this nearness, let alone understanding it, because all things increasingly present themselves to us as technological: we see them and treat them as what Heidegger calls a “standing reserve,” supplies in a storeroom, as it were, pieces of inventory to be ordered and conscripted, assembled and disassembled, set up and set aside. Everything approaches us merely as a source of energy or as something we must organize. We treat even human capabilities as though they were only means for technological procedures, as when a worker becomes nothing but an instrument for production. Leaders and planners, along with the rest of us, are mere human resources to be arranged, rearranged, and disposed of. Each and every thing that presents itself technologically thereby loses its distinctive independence and form. We push aside, obscure, or simply cannot see, other possibilities.1

We can reasonably point to the instrumentalization of ourselves and each other as the root of so many ills that beset modern culture, from the mind-numbing effects of bureaucratic workplaces to the re-casting of child-bearing as a kind of resentful parasitism. It is no wonder that the seemingly complete victory by the numerate over the stubborn unknowability of the world grates at us: it implies that we have been overcome, as well. It suggests that we are fully knowable by some combination of our genetics, social situation, and the connectivity of the synapses in our mind.

What is worse is that the numerate are so often right. Yes, the actuaries actually can predict with incredibly accuracy the life outcomes of anyone about whom they have gathered enough data. Even if we did not believe them, we have only to check whether the life insurance industry is solvent. But this does not make them any less insufferable, and the fact that we have unavoidably become part of Heidegger's 'standing reserve' of the machine of the world is insult enough to galvanize any rebellion.

B. Productive Complexity to Sterile Simplicity

This victory of the numerate over the natural world is not complete, however. There are two aphorisms common among the numerate that both originate from British authors. The first from the physicist and mathematician William Thomson Kelvin: "What is not defined cannot be measured. What is not measured, cannot be improved. What is not improved, is always degraded." And the second from economist Charles Goodhart: "Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes." These two principles stand in tension. On the one hand, counting things is a prerequisite for improving them. On the other hand, if that counted value becomes a goal, it ceases to be a useful way to evaluate whether something is improving.

It was this contradiction in principles that bedeviled the nascent field of scientific forestry in 17th century Europe. The early modern state was preoccupied with the value of its nationalized forests, for the revenue from the sale of timber (as well as the use of the timber in military shipbuilding) made the question of forest management an existential one. But the forests were unruly and illegible: mixed species, of different ages, with rampant underbrush and dense plantings that made it hard to harvest, let alone evaluate. How much forest did the government own? It was relatively simple to describe in terms of acreage, but not every acre was created equal. What the government wanted to know was, what is the value of this timberland in terms of the board-feet of lumber that it could produce per annum?

What grew to assist the early modern state by answering these questions was scientific forestry. We are familiar now with the sight of large, regular stands of timberland: straight, seemingly endless rows of trees, all of the same age and species, with minimal underbrush or other inconvenient interruptions. This alien form began in the forests of Germany some hundreds of years ago. With these regular, monoculture plantings, foresters could experiment in almost laboratory conditions with different fertilizers, weeding regimens, species and variations, and tracking the impact of rainfall. Heidegger's use of the phrase 'standing reserve' to describe our transformation from subject to object is mirrored in forest management. It is perhaps no accident that we describe sections of trees in a forest 'stands,' or that they are commonly grown on 'reserves.'

The unintended consequences of this regime were recorded by the American sociologist James C. Scott in his book Seeing Like a State:

The great simplification of the forest into a "one-commodity machine" was precisely the step that allowed German forestry science to become a rigorous technical and commercial discipline that could be codified and taught. A condition of its rigor was that it severely bracketed, or assumed to be constant, all variables except those bearing directly on the yield of the selected species and on the cost of growing and extracting them. As we shall see with urban planning, revolutionary theory, collectivization, and rural resettlement, a whole world lying "outside the brackets" returned to haunt this technical vision.

In the German case, the negative biological and ultimately commercial consequences of the stripped-down forest became painfully obvious only after the second rotation of conifers had been planted. "It took about one century for them [the negative consequences] to show up clearly. Many of the pure stands grew excellently in the first generation but already showed an amazing retrogression in the second generation. The reason for this is a very complex one and only a simplified explanation can be given.... Then the whole nutrient cycle got out of order and eventually was nearly stopped.... Anyway, the drop of one or two site classes [used for grading the quality of timber] during two or three generations of pure spruce is a well known and frequently observed fact. This represents a production loss of 20 to 30 percent."

A new term, Waldsterben (forest death), entered the German vocabulary to describe the worst cases. An exceptionally complex process involving soil building, nutrient uptake, and symbiotic relations among fungi, insects, mammals, and flora—which were, and still are, not entirely understood—was apparently disrupted, with serious consequences. Most of these consequences can be traced to the radical simplicity of the scientific forest.2

The tragic case of the ecological collapse of some of these early forest stands is an example of Goodhart's Law in action. When one measure (yield) became the goal of forest management, it ceased to be a useful score for the value of the forest itself; as Scott put it, the variables "outside the brackets" of yield were warning of danger even as yields increased in the short term.

In the ferment of online discourse, the concept that European forests are tame and bucolic while American forests harbor mysterious and dark forces is common enough to have been immortalized in both low-brow and middle-brow form. As one Reddit commenter noted, "America has larger swathes of untamed forest than Europe, so the nature is a lot ‘deeper’ and a bit more wild." This statement is true. Intensive forest cultivation is thousands of years old in Europe, and only hundreds, at best, in North America. From one telling, the forest managers have wrung the sublime terror out of the European woods, but have not yet completed their work in the haunts of the American cryptids.

Thus the second danger of 'demythologizing': the magical unknown of some complex system is not a superfluous and fanciful tale of mystery but is instead a straightforward statement of uncertainty: we do not understand everything about how complex systems work, and we measure them (and tinker with them on the basis of those measurements) at our peril. By bringing some variable in a system under our gaze, and by pushing on that variable to make it go up, we squeeze the life out of the system.

C. Visibility Is Control

English political philosopher, social reformer, and polymath Jeremy Bentham had another lawless and uncontrollable system in mind when he proposed a theoretical work of architecture that he believed could tame it: the prison. To him, the problem of unruly and expensive prisons stemmed from how opaque the prison population was to the warden and his many guards. Cramped in dark warrens of stone, prisoners were trapped but essentially invisible to their captors when not being surveilled directly. To Bentham these prisons were unhygienic for the body as well as the mind and soul. What was needed was to bring the light, both literal and metaphysical, to bear on the prison population.

By cleverly arranging a cylindrical prison with cubbyhole-like cells on the outer shell of the cylinder and a guardhouse at the central axis, a single guard could, at any time, see into any nook and cranny of the entire prison with just a glance. Louvered panels would ensure that he could look in any direction without tipping off the prisoners where he was looking at any one time. The prisoner would thus always be on his guard, attending to the hygiene of both his body and soul, because at any moment the unseen gaze of the warden could be falling on him.

Bentham, it should be said, was a social reformer keen to understand and remake the world along rational and utilitarian lines. In a letter outlining the key points of the plan, he forecasted that such a plan would have a psychological impact on the objects of the warden's scrutiny: "You will please to observe, that though perhaps it is the most important point, that the persons to be inspected should always feel themselves as if under inspection, at least as standing a great chance of being so, yet it is not by any means the only one."3

Michel Foucault, writing some hundreds of years after this speculative project was proposed, read in Bentham's proposal for the surveillance of a prison population the whole scheme of modern bureaucratic social sciences:

I am not saying that the human sciences emerged from the prison. But, if they have been able to be formed and to produce so many profound changes in the episteme, it is because they have been conveyed by a specific and new modality of power: a certain policy of the body, a certain way of rendering the group of men docile and useful. This policy required the involvement of definite relations of knowledge in relations of power; it called for a technique of overlapping subjection and objectification; it brought with it new procedures of individualization. The carceral network constituted one of the armatures of this power-knowledge that has made the human sciences historically possible. Knowable man (soul, individuality, consciousness, conduct, whatever it is called) is the object-effect of this analytical investment, of this domination-observation.4

Put another way, Bentham's Panopticon is a useful analogy for the way the whole of human population has been transformed into a standing reserve, made "docile and useful" for a host of bureaucrats, scientists, policymakers, and other meddlers. You know, the numerate. Modern science, statistical methods, ledgers and accounts, vital statistics databases, surveillance, and the all-seeing eye of social media algorithms conspire together to make our lives managed, scrutinized, experimented-on, and meddled-with in innumerable ways. This sense that modern life has had its magic snuffed out by pesky middle managers with rulers and clipboards is palpable.

And as Foucault argues, this meddling is not annoying merely, but is profoundly transformative of the human soul. It has changed the way that we conceive of ourselves as individuals, as bodies, as souls, as the docile and useful homo economicus of so many first-year microeconomics word problems. It has made us knowable; reducible to the demographic information that can so accurately predict the unfolding of our lives. We are no longer souls, but minds operating the machinery of our bodies in productive arcs through the course of life. The smug disciples of Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein5 have found ways to "architect our choices" in an invisible and compelling way with a kind of libertarian paternalism that is sensed more than seen.

Our beggared imagination can devise no alternative to this managed life but the madman: the raving cast-off lunatic following his protean, animal urges into the grimy interstices of manicured modern life, there being no wilderness that would be his proper repose. We pity him even as at some deep level we want to rebel, too, against our social media algorithms, the KPIs and performance plans from work, the credit score evaluating our trustworthiness with a single number, the damned two-factor authentication, the serene confidence and apparent competence of the chatbots increasingly scaffolding all aspects of our lives.

We resent this control and management, sensing that it has stolen something fundamental from us, but we are also so utterly held in the sway of the world the numerate has made for us that we can conceive of no alternative. The conversion of the world: its trees, its people, its bits and atoms, into a standing reserve, has worked, so far beyond our wildest dreams. Even the jilted witches of Stephenson's D.O.D.O. have to admit it. The ur-cause may be the stupefying excess value created in the world, reflected in (you guessed it! a number!) gross domestic product. From this fount all things flow: we live in a time of profligate wealth, luxuriant ease and comfort, and a bizarre military détente. You have to hand it to the nerds. Somehow, their spreadsheets and decennial reports and experiments and brow-beating public health advice has actually worked. They have actually delivered the magical effects our forebears sought.

And what is the downside? The forests may be denuded of their magic, but on the other hand, they are denuded of their magic. The faeries are gone, it is true, but so are the old malignant gods of the earth. The infant blood on their cruel altars has long since been washed away.

II. What Science Cannot Tell Us

If there is any indication that not all is well, that the transformation of the world from man to managed has had its downsides, we need look no further than the infants. Far more die at the hands of the numerate, in clinically benign and emotionally detached manner, than ever did in Mesoamerica or the ancient near East or the forests of Old Europe. Many more still remain arrayed in rows, a literal standing reserve of fertilized embryos awaiting their fate, in clinics and cold storage facilities worldwide. We apply the best analytical frames numeracy has given us: genetic screening that lets us select only those traits likely to give us the most vital, attractive, tall, healthy, as our offspring. The rest disappear, invisible to us now as they day they were conceived. One of the geniuses of numeracy is that it enables us to differentiate, specialize, delegate, sequester, and externalize. Our waste disappears from the curb each week; our spent water disappears into the ground; our unwanted embryos might as well never have existed, for all we know. And for all this, the world faces a slow-motion catastrophe of childlessness that will explode over the next several hundred years like a bomb inside of every nation-state, seemingly in proportion to how truly numerate the population grows. Numeracy makes us ever more capable of caring for our children, and ever less likely to even meet them.

This is the cold truth of our riven world: the same techniques that heal can also harm. The statistical methods that help us scratch at truth can also lie with more force and facility than we can on our own. Our dawning understanding of the human genome is at once making it easier to detect, prevent, and heal diseases and making it easier to exterminate those at higher risk of them before they can be born. Advances in artificial intelligence are scaffolding breathtaking discoveries in many scientific fields even as they gnaw away at our actual intellectual capacity.

Futurist and author Arthur C. Clarke most famously noted that “[a]ny sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Andy Crouch, writing about the relationship between technology and magic, said: “It is amazing how often Clarke’s dictum is quoted with unironic reverence, as a genuine guide to the direction that the human race should go. In fact, anyone who really understood the distorting history of magic—its tendency to displace God, its quest to enslave nature, its recurring obsession with fashioning beings to serve the magician, and above all its stunningly consistent failure to actually deliver on its promises—would hope that a sufficiently advanced technology would be very readily distinguishable from magic.”6

What are numeracy's shortcomings? I want to here apologize for smuggling in a subtle change to the use of the word numeracy. I have spoken of the numerate: those who can understand and use statistical methods, deduce and induce, understand the principles of scientific inquiry and the scientific method, and who are aware of and cautious of that nagging subjectivity and bias in their own thinking. But I am beginning now to mean something specific by numeracy, which has elsewhere been called scientism or technopoly: the tendency for can to substitute for should, for the technician to crave power, and for the tools of technique to be turned on humans.

A. Numeracy Does Not Tell Us What to Do with Its Techniques

Author and professor Alan Jacobs wrote:

I call [the regime built on technocratic rationalism] the Oppenheimer Principle, because when the physicist Robert Oppenheimer was having his security clearance re-examined during the McCarthy era, he commented, in response to a question about his motives, “When you see something that is technically sweet, you go ahead and do it and argue about what to do about it only after you’ve had your technical success. That is the way it was with the atomic bomb.” Social constructionism does not generate this Prime Directive, but it can occasionally be used — in, as I have said, a naïve and simplistic form — to provide ex post facto justifications of following that principle. We change bodies and restructure child-rearing practices not because all such phenomena are socially constructed but because we can — because it’s “technically sweet.”7

Or, to put it as bluntly as Dr. Ian Malcolm did to the eccentric numerate billionaire John Hammond in the film based on Michael Crichton's Jurassic Park:

John Hammond: I don't think you're giving us our due credit. Our scientists have done things which nobody's ever done before...

Dr. Ian Malcolm: Yeah, yeah, but your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could that they didn't stop to think if they should.8

We may as easily ask this question—“why?”—of those who design Internet-connected refrigerators as we do of those who boldly speculate about the dawning age of the cyborg. Post-humanist theorists such as Donna Haraway, even writing forty years ago, could accept the technological confusion of the age as a kind of received wisdom, taking the conditions of modernity for granted and speculating about what the cyborg could be in a world without clear distinction between animal and human, machine and human, human and human. But it does not follow, unless one takes for granted that there is no ought around which the world must turn. For those who sense there is such an axis, numeracy does not supply one, and numeracy in its absence is a freak show.

B. Numeracy Intoxicates by Its Power

What Foucault detected in Jeremy Bentham's prison concept, and indeed saw in every corner of the conditions of modernity, were the misuses of coercive power to transform individuals under its control. An unlikely bedfellow in this radical view was C.S. Lewis, who wrote in The Abolition of Man:

From this point of view, what we call Man's power of Nature turns out to be a power exercised by some men over other men with Nature as its instrument. [...] In reality, of course, if any one age really attains, by eugenics and scientific education, the power to make its descendants what it pleases, all men who live after it are the patients of that power. They are weaker, not stronger: for though we may have put wonderful machines in their hands we have pre-ordained how they are to use them.9

The body thrills at the experience of power indwelt when it apprises the ability conferred on it by technology. There is a reason Oppenheimer called this feeling "sweetness": there is nothing like a problem solved just-so. Numeracy's critics often miss this. There is a pure and fulsome satisfaction in true technical work, wholly separate from any kind of final goal. Numeracy is a heady wine, obscuring its effects and justifying itself by its very pleasure. It is no wonder that it is dangerous.

C. Numeracy Sets Itself Up as the Enemy of Humanity

There is a truth hidden in the populist bellyaching about those in the ivory towers, the coastal elites, the snobby professors. These epithets paint the numerate as enemies of real, red-blooded humanity, a criticism which must sting. After all, these are fellow humans we are talking about! Aren't we all on the same side, at some deep, fundamental level? It depends. The scientist who converts his fellow humans to one of Heidegger's "standing reserve" both betrays himself as an enemy of his common humanity, and places himself alongside them in cold storage. Again, Lewis:

We reduce things to mere Nature in order that we may 'conquer' them. We are always conquering Nature, because 'Nature' is the name for what we have, to some extent, conquered. The price of conquest is to treat a thing as mere Nature. Every conquest over Nature increases her domain. The stars do not become Nature till we can weigh and measure them: the soul does not become Nature till we can psychoanalyze her. The wresting of powers from Nature is also surrendering of things to Nature. As long as this process stops short of the final stage we may well hold that the gain outweighs the loss. But as soon as we take the final step of reducing our own species to the level of mere Nature, the whole process is stultified, for this time the being who stood to gain and the being who has been sacrificed are one and the same. This is one of the many instances where to carry a principle to what seems its logical conclusion produces absurdity. [...] It is the magician's bargain: give up our soul, get power in return. But once our souls, that is, ourselves, have been given up, the power thus conferred will not belong to us. We shall in fact be the slaves and puppets of that to which we have given our souls. It is in Man's power to treat himself as a mere 'natural object' and his own judgements of value as raw material for scientific manipulation to alter at will.10

Echoes of this sentiment are also found in Crouch’s work. To show the danger of magic, and technologies indistinguishable from it, he noted: “[t]he quest for magic does, after all, lead to encountering a kind of power—but it is one that masters us, not the other way around.”11 The techniques of our numerate practice can as easily turn on us as we use it to turn on our fellow humans.

III. What We Can Learn Nonetheless

When Oppenheimer said that making the atomic bomb gave him some kind of pure technical pleasure, what was he talking about? Was that ‘technical sweetness’ merely the pathetic sensations felt by a monomaniac? Perhaps something more solid and substantial was at the base. As he neared the heart of things, what gave off that sweet taste? What played that swell of chords? It is the sign of a small mind, the mind of a technician only, that they experience only the cheap thrills of some small task completed, and sense nothing of the whole. It is like someone who exults at the perfect fit of piece in puzzle but never steps back to gaze at the resulting picture. "I was right!" Right about what? That the piece fit there? Or that the composition coheres into something else entirely?

I am convinced that at the heart of true numeracy is awe. Lewis wrote something of this: "It is not the greatest of modern scientists who feel most sure that the object, stripped of its qualitative properties and reduced to mere quantity, is wholly real. Little scientists, and little unscientific followers of science, may think so. The great minds know well that the object, so treated, is an artificial abstraction, that something of its reality has been lost."12 An awe of this kind is not the innocent wonder of the novitiate but something far brighter and wilder that arises from true mastery.

And so, counterintuitively, the response to the depredations of numeracy as it is practiced by the behavioral economists, social scientists, scientific managers, and technocrats is not to stop up their great machines, as Ned Ludd and his Luddites did. It is to instead challenge them that they are not curious enough. It is to ask them to keep digging and searching, to try even harder to reach the truth behind the truth. Max Planck, the theoretical physicist and discoverer of the quantum theory used so creatively in D.O.D.O. by Neal Stephenson, predicted what they would find: "Science cannot solve the ultimate mystery of nature. And that is because, in the last analysis, we ourselves are part of nature and therefore part of the mystery that we are trying to solve." There is nothing so dangerous as a boorish, pedestrian, and incurious science; a cheap and cruel numeracy with impatient men at the helm. And there is no antidote like patient curiosity, the quality that drew so many of them to their fields in the first place.

Our anxieties are justified: the magic has gone out of the world. But it is not because the numerate squeezed it out, it is because they found something initially useful and stopped squeezing. The lens of Berkowski's modified telescope pointed to the heavens, a place of such abiding mystery that no photograph could ever freeze the magic out of it. Its very infinitude guarantees the mystery, what Planck called the ultimate mystery, that we are ourselves part of.

In a very different work from his repertoire, C.S. Lewis wrote an account of a man experiencing untrammeled outer space for the first time:

"The Earth's disk was nowhere to be seen; the stars, thick as daisies on an uncut lawn, reigned perpetually with no cloud, no moon, no sunrise to dispute their sway. There were planets of unbelievable majesty, and constellations undreamed of: there were celestial sapphires, rubies, emeralds and pin-pricks of burning gold; far out on the left of the picture hung a comet, tiny and remote: and between all and behind all, far more emphatic and palpable than it showed on Earth, the undimensioned, enigmatic blackness. The lights trembled: they seemed to grow brighter as he looked."13

The sun, moon, and stars are signposts of every episode in our narrative. At first, their movements stupefied and entranced; later we charted their courses and punctured all superstitions attending them. But the numerate may want to continue looking, learning, and wondering. May the lights grow brighter as they look; may the stars earn the name heavenly bodies.

https://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/understanding-heidegger-on-technology

Scott, James C. Seeing Like a State : How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Panopticon_or_the_Inspection-House

Foucault, Michel, 1926-1984, author. Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books, 1995.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nudge_(book)

Crouch, Andy. The Life We're Looking For: Reclaiming Relationship in a Technological World. New York: Convergent Books, 2022.

https://www.thenewatlantis.com/text-patterns/prosthetics-child-rearing-and-social

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0107290/

Lewis, C. S. (Clive Staples), 1898-1963. The Abolition of Man; or, Reflections on Education with Special Reference to the Teaching of English in the Upper Forms of Schools. London: Oxford University Press, H. Milford, 1944.

Lewis, The Abolition of Man.

Crouch, The Life We’re Looking For.

Lewis, The Abolition of Man.

Lewis, C. S. (Clive Staples), 1898-1963. Out of the Silent Planet. New York: Collier Books, 1965.